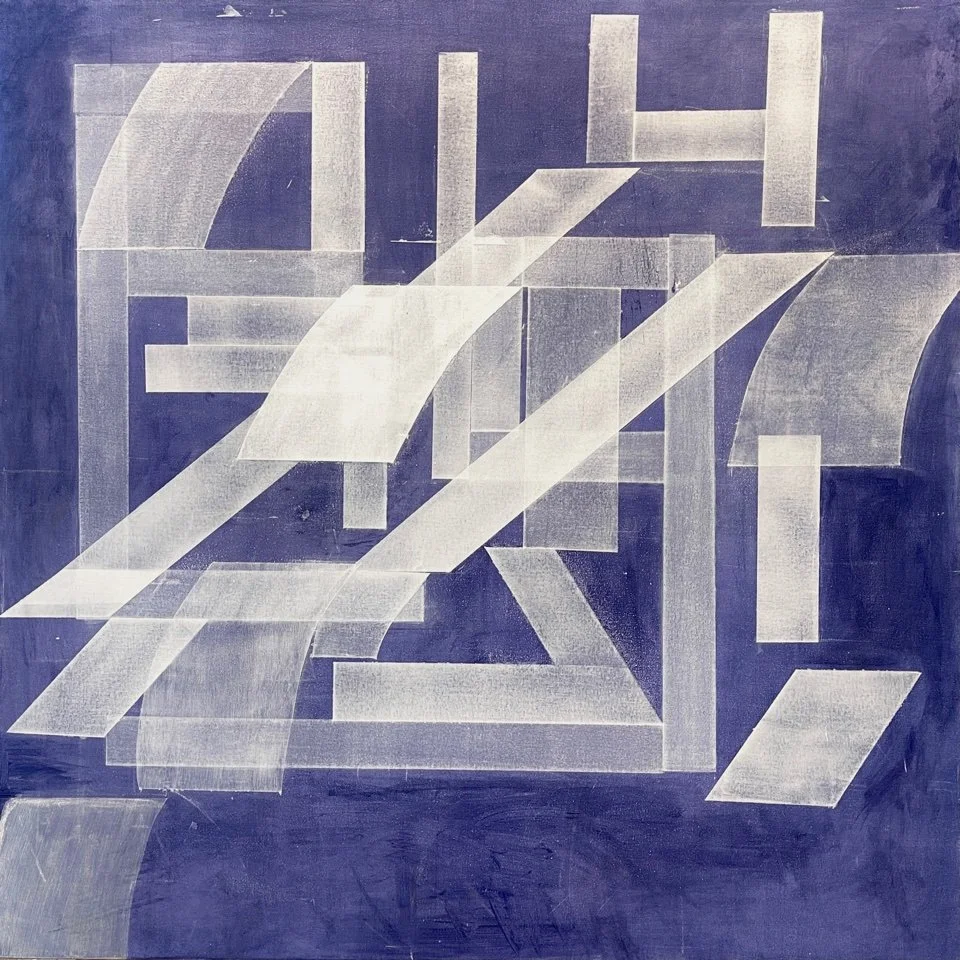

The 13 paintings that fill the front gallery have evolved from Ehrlich’s "disappearing paintings" of 2019, those comprised of loose whiteish gauzy translucent swaths against a monochromatic background. In these current works, however, the light swaths are more sharply delineated, as if lensed and now reappearing. These bands of white vinyl-based paint are set on a background field of a single acrylic color with fluctuating gradations, typically a light color more serious than pastel. Ehrlich does not succumb to the temptation to add additional notes of a different color. She builds these paintings by layering, which she describes as "a slow process...with nuances of accidents of application... [and] imperfections of surface as [she builds} the overlapping networks of light with paint. Each stroke rests on the one beneath as this process begins to resonate with light."

What are we looking at? Perhaps these swaths are letters, pre-words? Our first seeing--when we started crawling--likely was wordless, nameless. When we first learn to name what is in the seen world, we mimic the names of things, then we recall them, and then we speak them--but that knowing is a slow process forward with many steps backward, before letters have yet occurred to our minds. As adults, we are pretty amnestic to that time situated between seeing and naming. We may not remember, but we can recognize that zone in infancy between seeing and naming--and that zone also may come up in half-dream states. In these paintings do we see letters-- A V, C, L? Hebrew letters? Pictographs, glyphs of light, but definitely not words, and not things.

Or here, maybe an animal, an animal's ear? It is normal to see patterns in random data--a face in a cloud or a pile of clothes. That's termed pareidolia, the seeing of things in complex patterns. Our brains normally do that--we can't help ourselves! Some of these paintings are lithely simple, and some are complex though not complicated. However no pareidolia was deliberately depicted here. Ehrlich’s consistent abstraction fights off imagery ("this looks like a dog"), psychology (this is from my childhood), autobiography (this event happened to me). She is not pushing any particular emotional envelope in these works, except perhaps retinal bliss, a bliss that we recognize, akin to mathematics and music.

Notes by Sandy Moore