“Life is Long; Life is Short” is the descriptive title of this moving exhibit at Time & Space Limited in Hudson ---and it is certainly an apt descriptor. The strength of this work, comprised of 32 paintings, lies in its ability to embrace contradictory issues/ideas/realities, simultaneously and joyfully. The result is that it allows the observer to subject-to-doubt accepted historical truisms, mere linear thinking, and, above all, to focus on doubt while also presenting the possibility of hope.

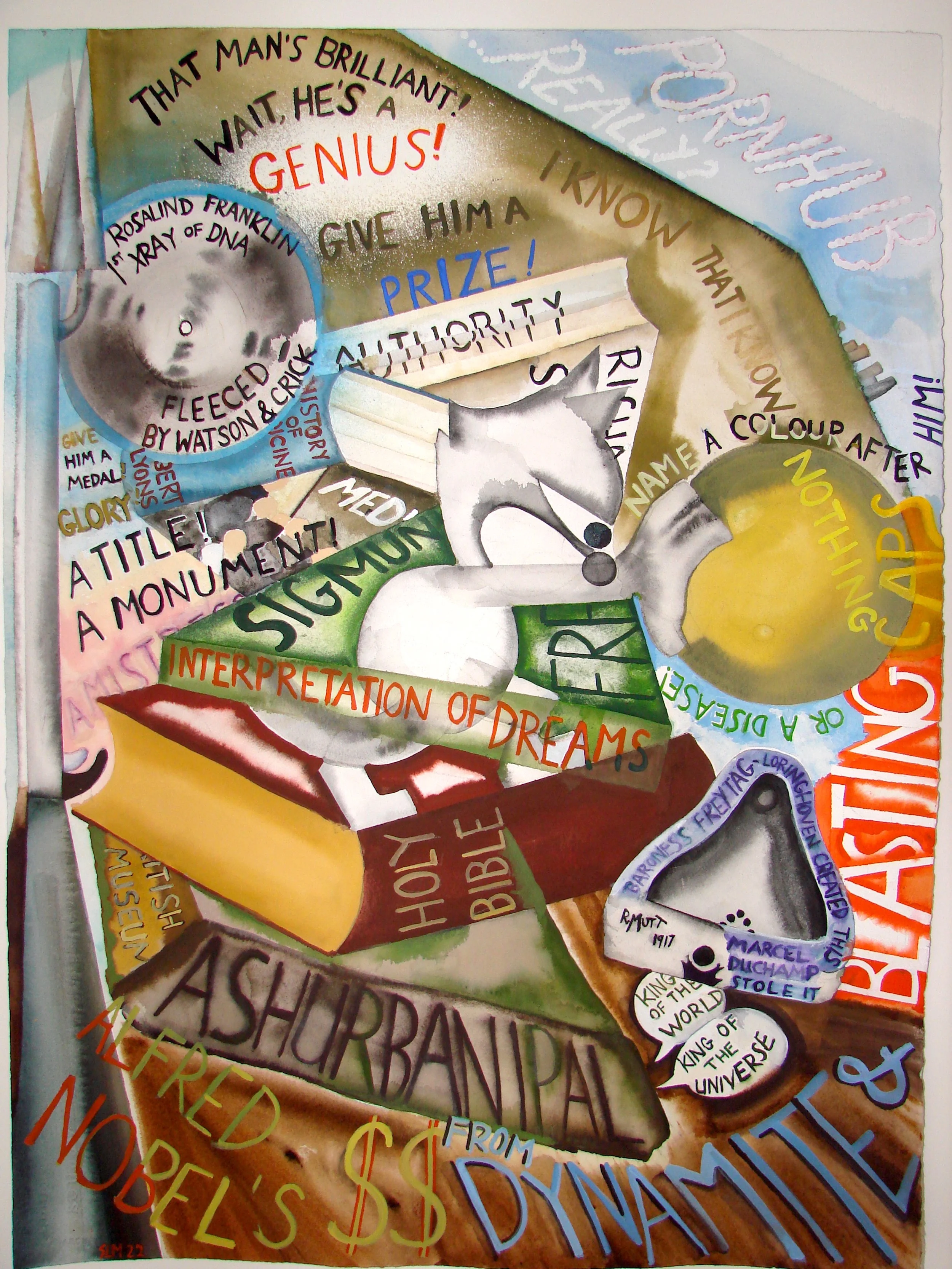

Subjected to doubt here are accepted historical truisms--for example in the depiction of the historical erasure of women, in an image which features Xray proof of DNA by Rosalind Franklin of Cambridge University, and the readymade "fountain" by Baronness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (allegedly appropriated by Duchamp)."Men's Work" and "Women's Work" gives the lie to these women's erasure. By recognizing them, powerfully, and defiantly, this exhibit grants them the space they deserve, thereby refusing to accept their selective historical disappearance.

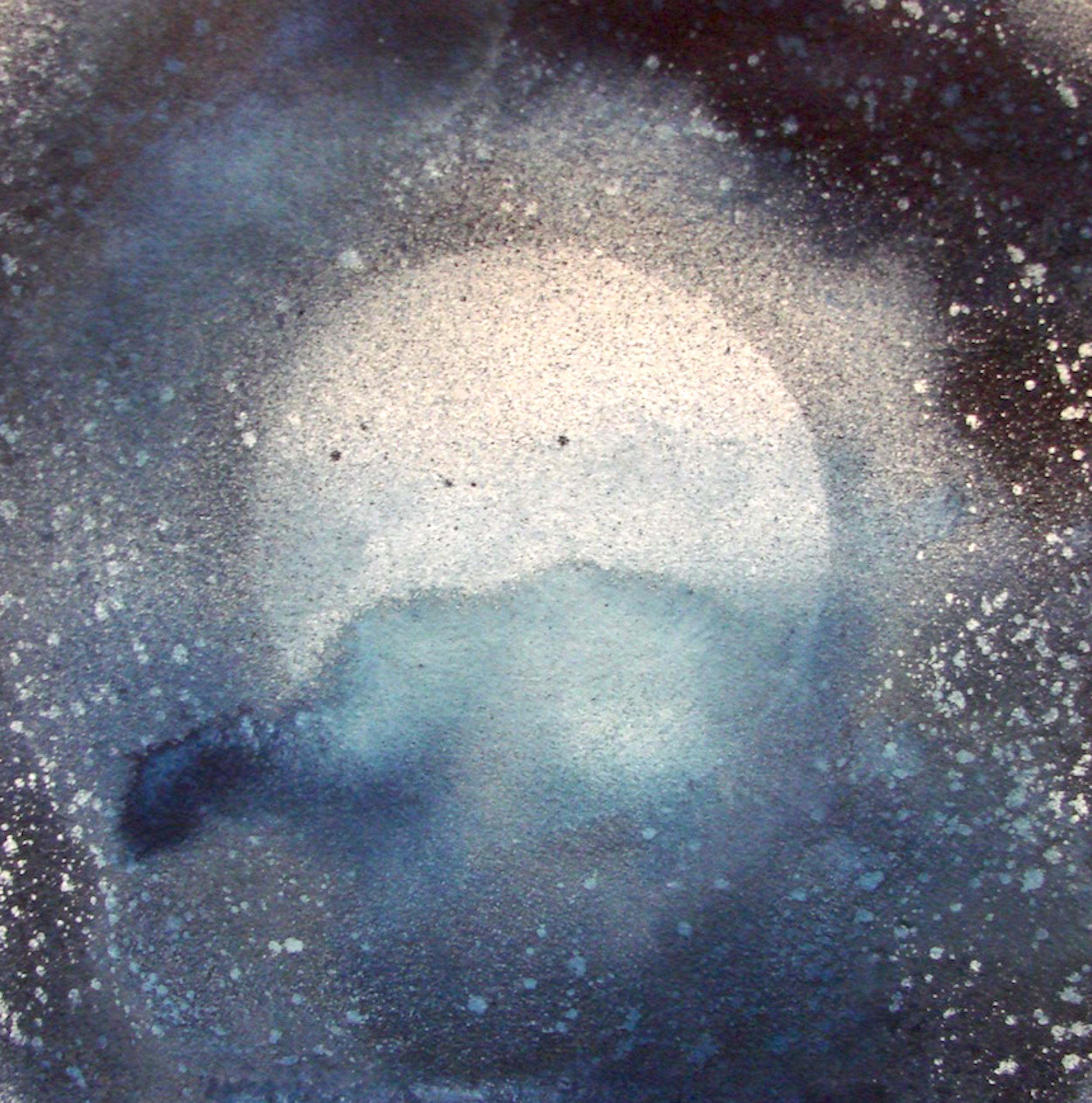

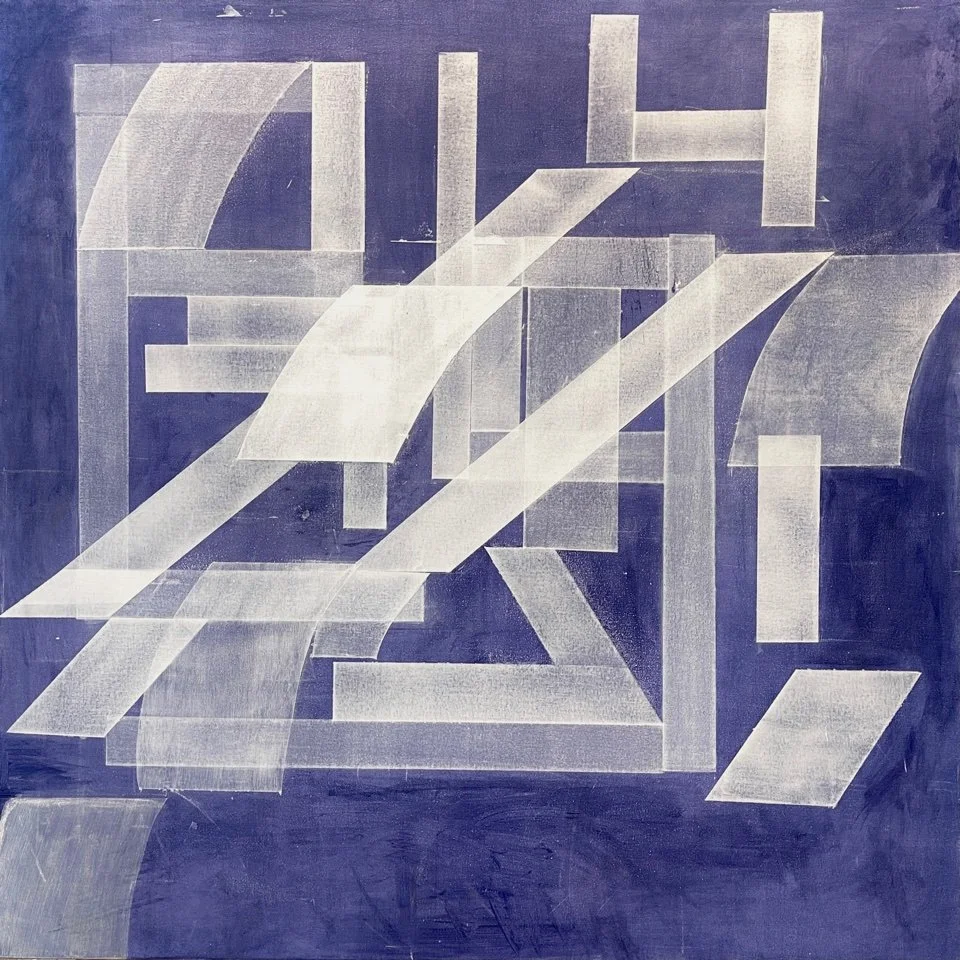

What the exhibit does to accepted truisms, the beautiful Bardo sequences do to mere linear thinking. They image, pictorially, the “Ah” of the “Now” while hovering over other-world possibilities in the “in-between-ness” of the Bardo images. The “conversation” this allows has a dual resonance: it makes palpable, and embraces, two different realities simultaneously: the physical and the primarily-spiritual that the Bardo suggests. At the same time, it provides a space wherein a “conversation” can take place between observer and work observed.

It is in this context that the 17th century writer, François de la Rochefoucauld, comes to mind in a remark he made that is applicable to this deeply-meaningful exhibit: “ Everybody looks at what I look at,” he said, “but few see what I see.” Showing seeing is crucial to an exhibit that encapsulates, pictorially, a meditative pause in our everyday thinking in order to invite us to see anew, to encourage what Dante Alighieri called a "novella vista". It subjects to doubt accepted wisdom while simultaneously engaging the observer in ways of seeing that engender a deep sense of hope.

Yvonne Jehenson Dunn, Retired Professor of Comparative Literature and Culture, Hudson NY

Women’s Work

Men’s Work

In Between/Bardo